Basics of Design

Formal Upright

by Lew Buller

There is only one formal upright in my collection, and that’s my bald cypress (Taxodium distichum). A formal upright requires a perfectly straight trunk and they are hard to come by. Even my bald cypress is not perfectly straight.

It grew in the ground for the first seven years of its life and could not be rotated to make sure all sides received the same amount of sun. The hormone auxin causes plants to bend toward the sun and so there is a slight bend in the bald cypress. To see the bend, you would have to see the tree from the side.

Wikipedia

In nature, the California redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) are about as straight as you will find. The tallest, at 379 feet, appears to be perfectly straight. Apparently the biological mechanism causing the tree to grow tall to get more sunlight outweighs the effect of auxin that bends the tree toward the sun. (For the record, there is a Redwood bonsai in the Brooklyn Botanic Garden) The extreme example of plants seeking sun is the sunflower. It will have its face pointed toward the sun in the morning, turn to follow the sun all day, and end up facing the sun as it goes down.

There’s a message here. Rotate your bonsai no less than once a month and once a week is better unless there is an overriding reason not to do so. Having light growth on one side of the tree is a reason; leave that side of the tree facing the sun until growth evens out. Sun has a tremendous influence on plants and descriptions of plants in nurseries will give the plants’ requirements for sun. Plants will grow in darkness, but it causes etiolation, i. e., long internodes and an unhealthy color due to lack of chlorophyll.

.

In San Diego, the Italian Cypress (Cupressus sempervirens) grows tall and straight, straight enough to meet the requirements for a formal upright. The variants ‘Stricta’ and ‘Glauca’ are especially dense, narrow, columnar trees. I created an Italian garden but it proved difficult to maintain so I took it apart.The difficulty is maintaining the shape of the cypress.

Here’s an isolated segment of the garden.There are some problems you need to know about before trying to grow this tree. Start with a very young tree or else make sure the tree you have does not have a strong side branch like the one in this photo. It blends in with the outline, but it has prevented low growth from developing on the right hand side. Be prepared to learn a new trimming technique. Trim not on the outside of the plant but between vertical shoots to minimize width and retain the tight vertical outline. Vertical shoots may have to be shortened to fit in below other vertical shoots.

So what are we to do if we want a formal upright? Certainly we cannot do as suggested in writings about Japan; black pine growers there allegedly hit the side of the tree, knowing that injury causes the tree to respond with growth at the injured site. I do what I have done all my life: my best, and this may include compromise and faking it. Here’s an example, a Chinese Hackberry. In full dress, it looks like this:

But its winter silhouette looks like this:

Very few of us look good naked; all of our flaws are evident. In the case of the tree, it was cut off and left to grow a new leader. I am still working to develop the leader so the transition between the area below the cut and the area above is smoother, less drastic.

In the material on informal upright trees, I pointed out that branches originate on the outside of a curve. Where do they originate if a tree has no curves? The practice is to have the first branch originate about one-third of the way up the trunk, with a pattern of left branch, back branch, right branch, repeating the pattern all the way to the apex. The spiral starts with either the left or right branch, never the back branch, and spacing gets closer together as the spiral moves toward the apex. By using this pattern, you draw on the experiences of viewers to make your bonsai appear taller. If you were looking at a tree at ground level and looked up, it would appear that branches higher on the tree are closer together.

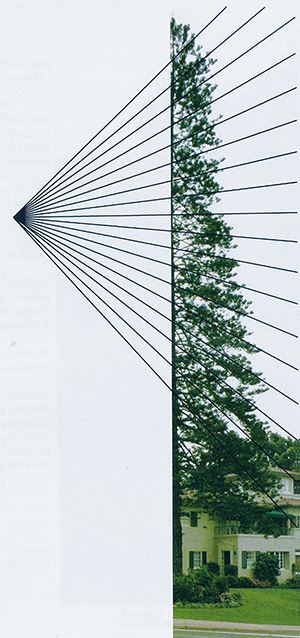

Do the branches on formal uprights have to be stiff and straight? There is some latitude here; what is more important is that the bottom branches point downward, the middle branches point horizontally, and the top branches point up. This can be demonstrated with a photo of a formal upright in the ground. The tree measures nearly 3 feet across at the base and possibly 100 feet tall. It is a Norfolk Island Pine (Araucaria heterophylla).

Perhaps the angles will be clearer if we look at just the right side of the tree. The fully grown tree demonstrates precisely the way branches on a formal upright should be placed, although they need not be quite so close together.

In choosing which styles of bonsai to develop and/or acquire, there has to be a place for the personality of the enthusiast. It’s OK not to like all trees; I told you I don’t like the han-kengai and the world did not come crashing down on my head. Nor do I expect it to as others read this.

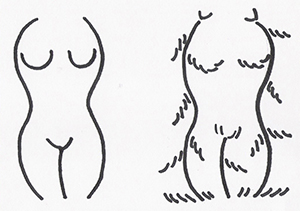

San Diego is not a place where there is a lot of formality. I go to nice restaurants in tennis shoes and without a tie, or in one case, after having just been caught by a wave at the beach that reached nearly to my waist. I have done the equivalent with my trees; they are mostly informal. In fact, I have definite preferences for curves in my trees. A woman friend of mine made a little drawing to express this preference. I told her the curves of a tree could be likened to the curves of a woman and here’s what she did.

Then she showed me a second drawing and said “I think this suits you better.

In neither case, did she put the branches on the outside of the curves. You can supply the captions for the second drawing. I hate to think what she would have drawn if I had expressed a preference for formal uprights.

To be serious for a moment, gender is used in bonsai to describe trees, pots, and stands. If you haven’t been thinking in those terms, look at some trees and pots and think which gender you would associate them with. Neither is better nor worse than the other; they are just a handy way to get consistency when planning to pot a tree. A masculine tree in a masculine pot; a feminine tree in a feminine pot. When it comes to stands, another scheme may help you. It has three alternatives: rough, intermediate, and refined. Again, the purpose is consistency. It doesn’t look right to have an elaborate stand with a very plain tree.

Herb Markowitz was the first person I ever saw work on a bonsai. I thought he was killing it. Later I learned it was Dr. Markowitz, that he had been a surgeon at the Naval Hospital in San Diego, and later the Chief Administrator of the same hospital. Herb had been a Japanese prisoner of war, but held no bitterness and certainly had a love for Japanese style bonsai. He died at 84 and his wife gave this juniper to the Mingei International Museum for its bonsai collection.

As curator, I took the tree home for some tender, loving care. It was the least l could do for a man who had done so much for bonsai in San Diego. It is a Foemina (Juniperus chinensis ‘foemina.’ Foemina junipers can be trained in the formal upright style and that is what Herb had done.

This was April 1, 2007 and I had some fast learning to do. Foemina junipers have a different maintenance schedule, are trimmed differently, and have growth forced differently than other junipers. From the end of June until the end of October, almost no trimming should be done on foeminas. If they are trimmed during this period, the trimmed end turns very brown and growth comes to a standstill.

Trimming and wiring can be done in November; properly wired, the tree can go for a year or more before wire begins to cut in. Old branches are brittle and do not lend themselves to bending easily. It is necessary to use raffia for severe bends and on larger branches, but smaller branches can be wired and bent without raffia.

Foeminas respond to fall pruning with substantial growth the following spring. The November pruning can be quite severe, so long as some green needles are left at the tip of each branch; otherwise, the branch will die.

Triple 16 Osmocote had been used in April to keep the tree growing and cottonseed fertilizer cakes used the following spring to provide balanced nutrition. Clearly, the tree had filled out but this was not the time to force growth.That would wait one more year.

To force new growth to sprout from inner, older wood, the following schedule needs to be observed in the spring. Let new growth develop to about one-half inch and then pinch the new growth off. Again let new growth develop to about one-half inch and then pinch the second round of growth off the tree. Do not pinch again; let the tree grow until November and then give it a pruning. The new, inner summer growth can be wired and trimmed as well as the previous year’s growth when this schedule is followed.

Because foemina needles are extremely sharp, it may be wise to use tweezers to hold the branch being shortened and cut the branch with scissors in the other hand. Latex gloves permit working directly with the needles.

If possible, transplant ever other year; if the soil is in good shape and the tree shows no sign of distress, it is possible to transplant every third year. Do it in spring, just as new growth is beginning to show. Trim roots lightly rather than heavily. Water thoroughly and do not water again until the soil has begun to dry out. Excessive watering in the weeks after transplanting will kill the tree.

Herb was Navy through and through. He had a beautiful boat that he had rigged so one person could handle it. I had to turn down his offers to join him as I got sea sick any time we left the bay.

It seems fitting to repeat the prayer that Herb had on a plaque in his boat.

“Oh Lord, it is such a big ocean and my boat is so small. Please take care of me.”