Basics of Design

Cascade Forms

by Lew Buller

Kengai is the Japanese word for cascade. Han-kengai is the word for half-cascade. In John Naka’s Bonsai Techniques I, he discusses various forms of cascades and illustrates them with drawings. Kengai, the regular cascade, drops about 450 but not in a straight line; the tip swings either left or right.

I have three cascades each shown at various stages of development. All three have significant flaws that keeps them from being perfect, but then none of my trees is perfect. The first is a small torulosa that has two problems. First, the torulosa does not bud back readily; second, the trunk is quite long before it begins to cascade. I tried shaping several torulosas by wiring them and bending them drastically and then couldn’t figure out what to do with them as they grew. This one seemed to have some future as a cascade, so I gradually tipped the trunk more toward the horizontal each time I transplanted it.

October 10, 2010 / July 2, 2014 / Han-kengai

It doesn’t wire mark quickly and the bark on the trunk is a beautiful old bark. It may be 17-18 years old; I got it along with some others, seven of which were used to create my saikei, “Torulosa Grove on the Seashore” for my book Saikei and Art. There are four others in different designs in my back yard. I have seen cascades with apices directly over the down-hanging branch, but did not want to do that. I continued to reduce the top until 2014.

Once in a while I will try a design using computer software, as I did here with the han-kengai. It’s too drastic a design for me, so I will not implement it. The next photo of this cascade will show work done, no computer software. It’s too late in the season to transplant this torulosa. There are advantages to looking at a photo of a tree before changing its shape. Live and up close, foliage makes the tree look good. In a photo, every flaw will stand out and can be considered in making the next change in design.

This trim leaves me with two options, and I will choose the one where the foliage develops better. Put your thumb over the top branch and you can see the potential for an ordinary cascade. Put your thumb over the bottom branch and you can see the potential for a han-kengai. That would be a first for my collection, as I am not particularly fond of this form; it looks unnatural.

The “stand” is a piece of a camphor tree stump that I helped take out while working as an arborist. I liked the color, the texture, and the smell.

The second cascade is a bougainvillea and it will be transplanted. Hot weather, July and August, is a good time for transplanting bougainvillea. It comes from Brazil, a hot country.

This bougainvillea cascade started out in a hanging wooden box. It didn’t thrive, so I took it out and planted it in a cascade growing pot, and then moved it into this bonsai pot. The trunk was larger than my thumb; anything smaller would likely not have survived transplanting. I later figured out that the reason it hadn’t prospered is that bougainvillea do not like to grow in a downward direction. In nature, they grow as a woody vine and may reach 30 feet in height.

It finally became so root bound in the cascade pot that I took it out and put it in a growing pot. It has been in the growing pot too long. The leaves don’t look good, and that says there is something wrong with the roots. The lower part of the tail is very sparse, but that is to be expected. One of these days, it may be so sparse that it becomes a half-cascade. In the past, I balanced it by keeping the top as small as possible so all of the carbohydrates could be available to the tail.

There is another possible problem. Old bougainvillea do not sprout back well, in the same way that black pines will not put out new growth on bark that is five years old or older. This cascade is old enough to vote. I bought it in 1991 as a 2-year starter.

When we (Eitan, the Apprentice and I) took the tree out of the pot, the roots were in bad shape. Very few of the size I was hoping for, not a lot of fine roots, and poorly developed on one side. These problems became clear when we took a hose and bare-rooted the tree. To make the tree fit its first cascade pot, I had cut off most of the roots on the back side, and they had not re-grown. That was made worse by tilting the tree more severely, giving even less room for roots. The soil was fairly coarse–it might have benefitted from more organic material.

None of the fine roots were removed. Everything that was alive was kept and transferred to the bonsai pot. The fresh soil was also coarse, but it had worked in the past. The angle of the cascade was opened up, not quite to the recommended 450 and the tree was wired in the pot. Soil covered the wires and was pressed lightly into place.

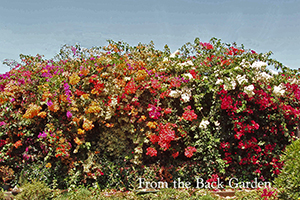

I planted the cascade bonsai at the same time that I planted 6 different colors of bougainvillea, 2 plants each, along the back fence. Bougainvillea really don’t like to grow down; they like to grow up. The same thing we all hope to do one day.

One bonsai master says a cascade should always be in a deep pot. The intent here is to imply the tree is on a tall mountain and is spilling down the side. Another master modifies that advice and says a much smaller pot is OK. I chose the smaller pot; the bougainvillea would die if the few roots is has were buried in a deep pot. In the final analysis, trust yourself.

The next cascade is also in a relatively small pot. Its flaw is that it was collected and potted by a beginner who did not understand the plumbing system of trees. In almost all trees, there is a direct connection between the roots below and the branches above on the same side of the tree. He was in a hurry to have a bonsai with shari (dead wood showing) and removed the bark all the way to the roots. You can see the entire top of the tree is dead and consequently the foliage is very sparse and dependent on only a few roots. (This is a good place to plug the best non-bonsai book that bonsai enthusiasts should have in their library. It is Botany for Gardeners, by Dr. Brian Capon and the 3rd edition can be found at various sources on the Internet.)

The tree is a San Jose juniper that originally was in a semi-erect position. I bought the tree to see if I could keep it alive and develop decent foliage. That was nearly 20 years ago. Each time I repotted it, I tilted it a bit more until finally it can be called a cascade. The long tip of the tree died due to lack of nutrients, so I am working with the one branch that still receives nutrients. The tip of the cascade drops below the bottom of the pot–when it was in half cascade form, it looked terrible. Look carefully and you can see the cork under the trunk where it crosses the edge of the pot.

It’s planted on the diagonal–that gives more room for the back roots to develop, except there aren’t any. I could hide the bare trunk by placing stones or accessory plants around it, but that wouldn’t make the point about not removing bark down to the roots. As it continues to fill out, the profile from the side will be more like the cupped hand of other trees. From the top, the shape will be more in a diamond shape.

The tree is wired in the pot, but lacking back roots, the only way to keep the trunk off the edge of the pot was to put something under it. The next photo shows the foliage looking down and you can see that with just a few snips, I can create a diamond shape. I would rather have the extra foliage than the perfect shape right now. When you’re looking, you will also see some wire–no way this foliage mass can be developed solely by the clip-and-grow method.

The San Jose is notorious for its prickly foliage. I use latex gloves to avoid feeling as if I were stuck by needles. There is another way. Grasp the branch slightly behind the point you intend to work on. Gently tighten your grasp while moving your hand forward. The needles will lie down rather than sticking up and stabbing your fingers.

Not all cascades need to be massive. Here’s one that most anyone could develop in a few years. The tree is a procumbens nana and the bark tells you that it has been around a while. Note that it is in a deep cascade pot and on a stand that emphasizes the height of a mountain location.